Originally posted by Thomas J. Cullinane Jr.

View Post

Announcement

Collapse

No announcement yet.

The Bundeswehr in Service outside of Germany

Collapse

X

-

Gents – Here’s a picture that I clipped from a now forgotten newspaper back in 1999.

It depicts a Bundeswehr infantryman warily advancing through the Serbian village of Novake in the now independent state of Kosovo.

Of note are the G-36 rifle and armored vest. Due to a general shortage of body armor, the Bundeswehr had to scramble to provide deploying soldiers with adequate personal protection. This set appears to carry the Dutch Disrupted Pattern Material (DPM) camouflage scheme, but I suppose it could be British as well. Note too, the integral magazine pouches at the front of the vest.

On his left shoulder we can the grass green band on the epaulette identifying him as a infantry man (I don’t know if he was a panzergrenadier or paratrooper) and what I believe to be a “dog tag” chain woven through the epaulette with the tags themselves seated in the small sleeve pocket. Please correct me if I’m wrong.

It never ceases to amaze me that in my conversations with old soldiers, when I ask what place was the worst, everyone I’ve spoken to, including veterans of hard fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq, always say the Balkans.

I passed through the Balkans a couple of times; Bosnia, Kosovo, Macedonia (“FYROM”) during my service. I never stayed long, but you didn’t have to realize something very, very bad had happened there.

A recent phenomena of the Global War on terror is the widespread extent of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in returning veterans. In looking at the eyes of this Bundeswehr soldier, one wonders if PTSD was widespread among Bundeswehr returnees from the Balkans.

Does anyone have any more information to add on the Bundeswehr’s combat experiences in the Balkans?

All the best - TJAttached Files

Comment

-

TJ,Originally posted by Thomas J. Cullinane Jr. View PostGents – Here’s a picture that I clipped from a now forgotten newspaper back in 1999.

It depicts a Bundeswehr infantryman warily advancing through the Serbian village of Novake in the now independent state of Kosovo.

Of note are the G-36 rifle and armored vest. Due to a general shortage of body armor, the Bundeswehr had to scramble to provide deploying soldiers with adequate personal protection. This set appears to carry the Dutch Disrupted Pattern Material (DPM) camouflage scheme, but I suppose it could be British as well. Note too, the integral magazine pouches at the front of the vest.

On his left shoulder we can the grass green band on the epaulette identifying him as a infantry man (I don’t know if he was a panzergrenadier or paratrooper) and what I believe to be a “dog tag” chain woven through the epaulette with the tags themselves seated in the small sleeve pocket. Please correct me if I’m wrong.

It never ceases to amaze me that in my conversations with old soldiers, when I ask what place was the worst, everyone I’ve spoken to, including veterans of hard fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq, always say the Balkans.

I passed through the Balkans a couple of times; Bosnia, Kosovo, Macedonia (“FYROM”) during my service. I never stayed long, but you didn’t have to realize something very, very bad had happened there.

A recent phenomena of the Global War on terror is the widespread extent of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in returning veterans. In looking at the eyes of this Bundeswehr soldier, one wonders if PTSD was widespread among Bundeswehr returnees from the Balkans.

Does anyone have any more information to add on the Bundeswehr’s combat experiences in the Balkans?

All the best - TJ

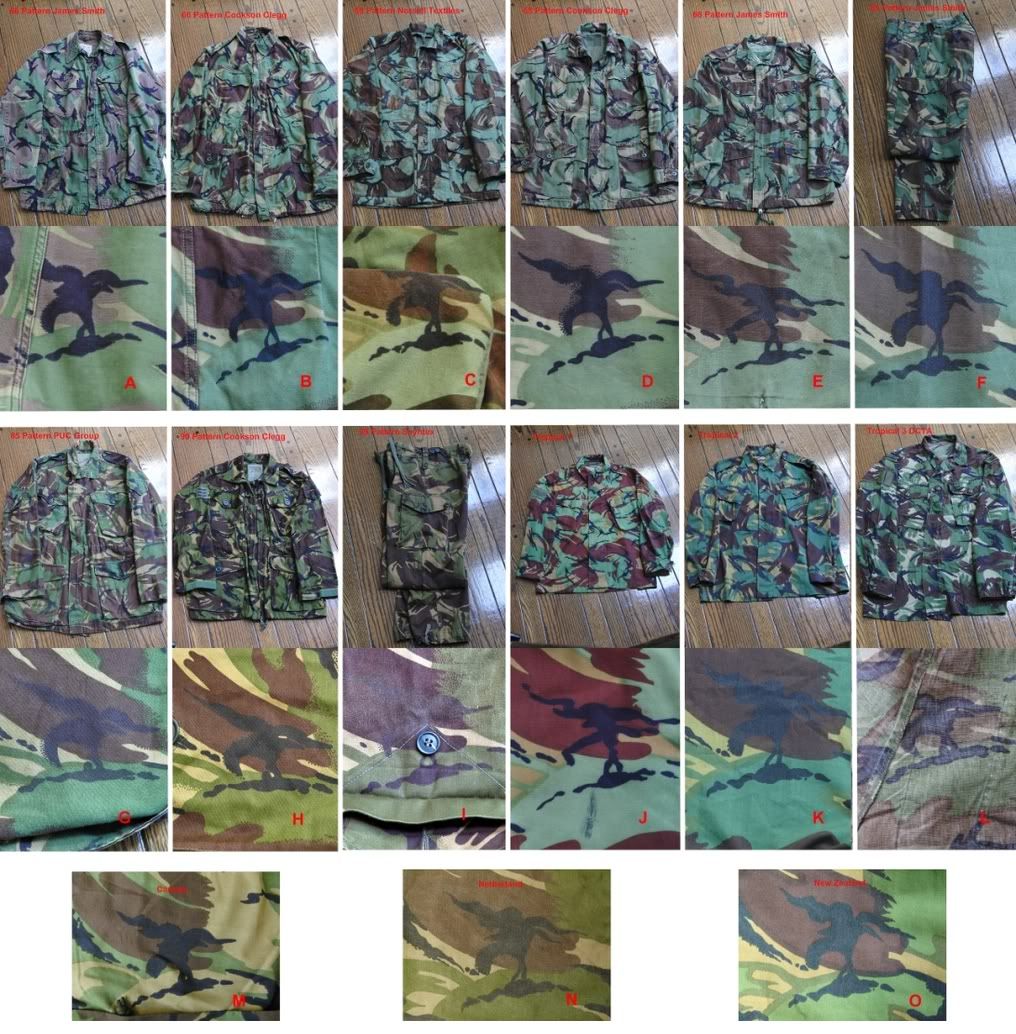

Hard to see exactly which country this cammo is from. Here are pictures of a Dutch and a British cammo jacket for comparison.

Regards,

Gordon

Dutch cammo first. To me it looks like the Dutch cammo as you first mentioned.Attached Files

Comment

-

Rich W. - Good catch; I think this was the one you had mentioned.

Well worth a read.

Thanks - TJ

New York Times

No Parade for Hans

November 14, 2009

By NICHOLAS KULISH

BERLIN — Often, as I have passed through the main train station here in the German capital, I have seen the sad, lone figure of a soldier, heavy pack on his back, waiting for a train like the rest of us, but separated from the crowd by the uniform he wears. No one would stop to thank him for his service or to ask whether he had been deployed to Afghanistan.

The loneliness was obvious, but at times I even sensed what I thought might have been fear, at the occasional hostile looks the soldier would receive alongside the impassiveness of the broader masses on the platform, who just tried to pretend he wasn’t there.

In Afghanistan recently, where German troops are engaged in ground combat the likes of which their military hasn’t seen since World War II, I described my impressions of the home front to a group of soldiers from a reconnaissance company.

A staff sergeant, who had been risking his life almost daily outside Kunduz, recalled a trip to Berlin during which he was wearing his uniform at a train stop. He was told to make himself scarce or he would be beaten up.

“It was shocking,” said the sergeant, Marcel B., who, according to German military rules, could not be fully identified. “We’re looked down on. With American soldiers, they tell me how they receive recognition, how people just come up to them and say they’re doing good.”

Last Wednesday, Chancellor Angela Merkel became the first German leader to mark the armistice that ended World War I with French officials in Paris.

It was one more sign of how far her country had come in repairing relationships with its former enemies, now its allies and partners. In fact, Germany carries the European sensibility about war — forged out of centuries of violence and in particular the 20th century’s devastation — even beyond where the French, the British, the Dutch and others do.

Instead of marking Veterans Day or Armistice Day on Nov. 11, Germany on Sunday observes Volkstrauertag, its national day of mourning for soldiers and civilians alike who died in war, as well as for victims of violent oppression. German society has a complicated relationship with war, due to the Nazi era. The result has been a generally pacifist bent and an opposition to most armed conflicts; that includes majority opposition to the Afghanistan mission, which often expresses itself as a mistrust of those in uniform.

In this, there is a profound contrast to current attitudes in the United States, where even opponents of recent military missions in Iraq and Afghanistan have taken pains to express support for the ordinary soldier who has been sent to fight and perhaps die.

The German men and women in Afghanistan set off for war without the support of the populace, and they know that when they return there won’t be crowds cheering in the streets, ready to make heroes of them. Germany has turned its back on hero worship. The soldiers fight alone.

“This sense of appreciation, you don’t get that, the feeling that wearing your uniform people are going to be proud of you,” said Heike Groos, who has written about her time as a German military doctor in Afghanistan. “Young people die. Young people are badly wounded and one feels out of place and lonely when one thinks, ‘No one in Germany understands and no one in Germany is even interested’ .”

The German military was revived in the 1950’s as a linchpin in the NATO barrier to Soviet expansion, but it was limited to a defensive role. Although they trained and took part in disaster assistance, German forces did not face combat until taking part in NATO’s Balkan campaigns in the 1990s. Now the German military is trying to come to terms with the radically different realities facing the professional soldiers in combat in Afghanistan (conscripts can be sent only if they voluntarily extend their service).

In July, Mrs. Merkel awarded four German soldiers who served in Afghanistan the first medals for bravery the country had given since World War II. In September, President Horst Köhler opened a memorial here in Berlin to all those who have died while in military service since 1955.

Daniel Libeskind, the architect of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, is redesigning the former East German military museum in Dresden to be used as the main military history museum of Germany’s military, the Bundeswehr.

And last week, Germany’s new defense minister, Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, traveled to Afghanistan, where he told the troops: “I believe that our common fatherland can be proud of you. I know that I am.”

But such official recognition of the changing circumstances is not the same as a broader acceptance in society.

“Support the troops” can start to sound like a hollow mantra until you live in a country that just doesn’t do it. In the United States, the little flags in store windows, the bumper stickers, the yellow ribbons around tree trunks and hanging on doors — not to mention the sense of national mourning that President Obama addressed last week after the mass shooting of soldiers at Fort Hood — weave together to form a kind of psychological safety net for soldiers.

To this American, the talk show hosts’ and football announcers’ greetings to the soldiers had begun to sound a bit obligatory until I returned from Afghanistan and started really paying attention to German television, hoping to catch just one similar gesture. So far I haven’t.

In the Vietnam era, the divisions within American society over the war meant that returning soldiers in uniform faced epithets from protesters. But a consensus has since emerged that decision makers should take the heat for war policies, and young men and women in uniform should be supported for the risks they undertake on behalf of the country.

Reinhold Robbe, the German Parliament’s military commissioner, said he remained impressed by the memory of seeing on trips to Tampa and Washington and El Paso that “complete strangers are buying soldiers beer.”

“There’s no real empathy in Germany toward the soldiers who risk life and limb every day,” said Mr. Robbe, 55.

Mr. Robbe’s own experiences track Germany’s complex mix of attitudes toward its postwar military. He refused to serve as a young man, saying he did not understand why he should shoot at relatives in East Germany. But as a member of Parliament in 1995 he became one of several dozen Social Democrats to cross party lines to support the Bosnia mission. As a result, his face ended up on posters with the words “the warmongers,” and Mr. Robbe found himself under police protection.

That was a time of open pacifism; what has taken its place is something different. “Compared to those days, we’re a bit farther along, a bit more used to it,” Mr. Robbe said. “But one basically leaves it in Parliament’s hands, and really wants nothing to do with it, and the soldier doesn’t get the moral support that he has earned.”

Comment

-

Gordon - I think you're right about this being a Dutch pattern camouflage vest.Originally posted by Gordon Craig View PostTJ,

Hard to see exactly which country this cammo is from. Here are pictures of a Dutch and a British cammo jacket for comparison.

Regards,

Gordon

Dutch cammo first. To me it looks like the Dutch cammo as you first mentioned.

Thanks - TJ

Comment

-

The British DMP and Dutch camo are the same, the Dutch adopted DPM after the British (The British got it in the 60s, the dutch much later, 90s?) The only difference between British and Dutch jackets is the cut, otherwise exactly the same.

Oh and Bristol is a city in England and the Bristol vests are made by a British company (Vickers if I remember rightly)

Phil

Comment

-

Uscha and Charlie Brown - Great info on the vest. Their origin had me puzzled for a good long time.

In the U.S. Army, the protective vest is referred to as "IBA" for Individual Body Armor. Like the "Bristol" vest, it isn't much good unless the ceramic plates are present. They are called "SAPI" plates for Small Arms Protective Inserts. These are inserted into internal pockets located in the IBA. Supposedly, the plates can stop a 7.62mm AK-47 round; I'm glad I never had to find if they worked or not!

In 2002, I made several visits to Eagle Base in BiH and Camp Bondsteel in Kosovo. For those trips I was issued with an older type "flak jacket". This vest might have stopped shrapnel, but there was no chance of it stopping a bullet. Luckily, things were very quite at the time and I spent just about all of my time behind the wire.

Below is a picture of a Bristol Vest clad BW Soldier standing next to an Orthodox Priest in Kosovo. The image was scanned from the excellent book "Das Heer im Einsatz" by Gerhard Hubatschek (ISBN 3-932385-12-8)

All the best - TJAttached Files

Comment

-

Dpm

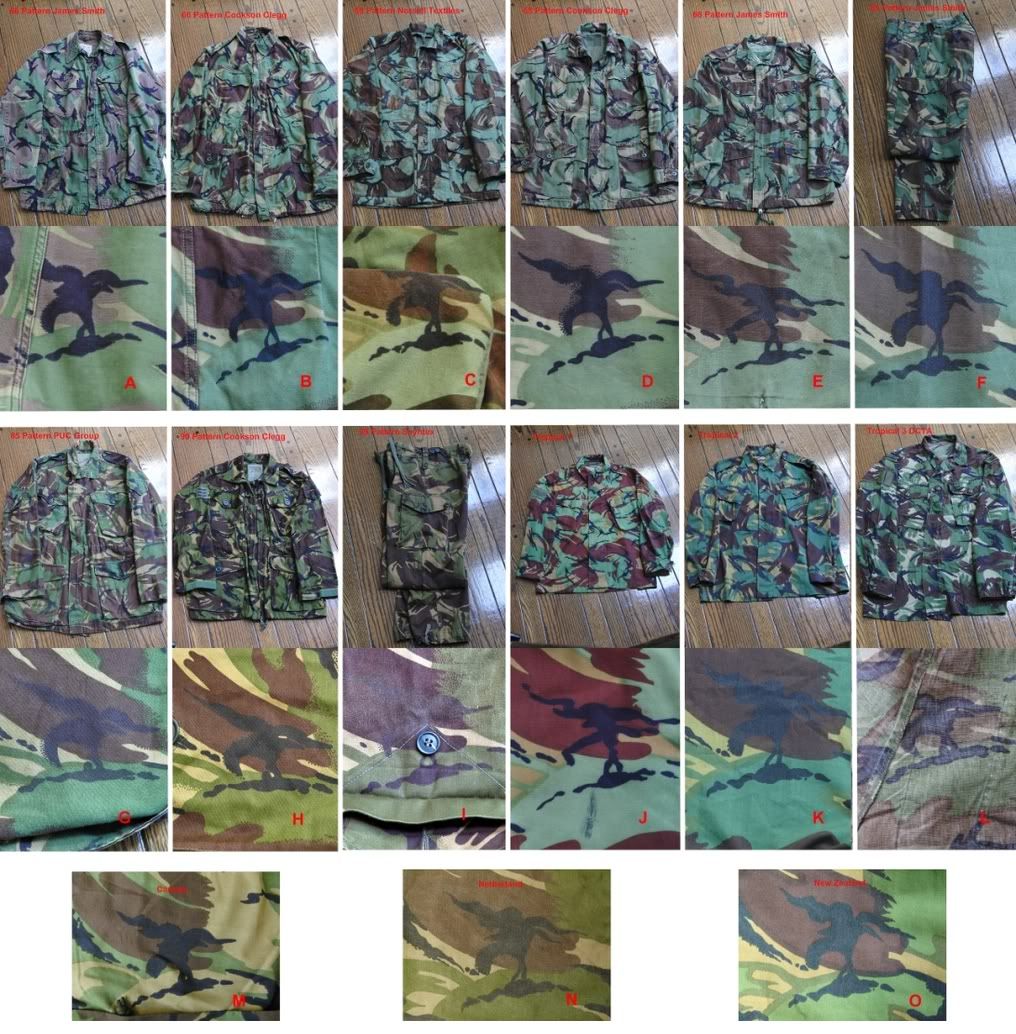

At the risk of going full bore on an off-topic tangent, I thought I'd add a few more words about DPM, a pattern with a remarkably long history that may yet outlive its association with the UK armed forces, thanks to its adoption by various other nations across the globe. While this topic might actually belong on the Commonwealth forum, I sense that in most of those collectors' eyes, the one and only British camo uniform worth collecting is the para smock, preferably Denison. Whereas evidence suggests the collecting taste among the regulars here may be a bit more eclectic.

From my limited observations, the DPM pattern appears to have undergone numerous small changes over the decades while in British service; some of these changes are more noticeable than others. As one can see below, even within the same model of combat smock (e.g., "A" and "B"" = 1966 model, "C", "D" and "E" = 1968 model), a surprising variety of sub-patterns can be seen.

Using one particular feature that I would like to call "Fishing Eagle", one can readily note the many similarities and differences between these DPM variants, which can be grouped into four major types:

1) Fat bird: A, F, K, M, N. O

2) Skinny bird: E, J

3) Fuzzy bird: B, C, D, I

4) Broken leg: G, H, L

Within these four major types, a number of subtypes can be differentiated based on features, in ways that are far less subtle than what helmet and medal collectors are accustomed to seeing when identifying various decals and pin shapes.

What is clear from this comparison is that the Dutch DPM ("N", and its New Zealander cousin "O") is a virtual copy of one sub-type of DPM pattern that appeared on 1968 model British combat uniforms, which was itself a derivative of one variant of the DPM patterns seen on 1966 model uniforms. It is readily distinguishable from the last pattern DPM in British service ("H"). As near as I can tell, the Dutch military adopted only one pattern and never made changes to it.

I am not sure why the UK designers felt the need to play with the DPM pattern so much over the years, since most of these differences begin to disappear at any distance beyond arm's length. Perhaps they thought they were designing collectibles for future generations of militaria enthusiasts?

Incidentally, I truly believe the 1968 model smock was the best combat jacket ever made, at least in terms of its design and build quality, as well as casual-wearing comfort. They are still relatively cheap and plentiful from ordinary surplus sources; I don't seem to be able to stop myself from buying more of them whenever I come across any, because "they" simply don't make'em like that anymore...

Gene T

Comment

-

Team - Earlier today CNN (known at this address as the "Communist News Network"), posted a video report on the German public's waning support for operations in Afghanistan.

While many of us may find the audio commentary somewhat dismaying, the video is outstanding. It features some fine film work of the Bundeswehr in pre-deployment training in the BRD as well as deployed in Afghanistan. There is a veritable feast of information for both vehicle and uniform aficionados.

The video also contains some poignant imagery from funerals of the recently fallen BW Soldiers, still shots of which Uscha was kind enough to supply us with on another thread.

For recent imagery of the BW in training and at war, follow the link below:

http://afghanistan.blogs.cnn.com/201...tion/?hpt=Sbin

All the best - TJ

Comment

-

Gene T - I for one am delighted with your "full bore" attack which I found extremely instructive and informative. You have obviously given this topic a great deal of thought and I thank you for sharing your painstaking research with the forum.Originally posted by Gene T View PostAt the risk of going full bore on an off-topic tangent, I thought I'd add a few more words about DPM, a pattern with a remarkably long history that may yet outlive its association with the UK armed forces, thanks to its adoption by various other nations across the globe. While this topic might actually belong on the Commonwealth forum, I sense that in most of those collectors' eyes, the one and only British camo uniform worth collecting is the para smock, preferably Denison. Whereas evidence suggests the collecting taste among the regulars here may be a bit more eclectic.

From my limited observations, the DPM pattern appears to have undergone numerous small changes over the decades while in British service; some of these changes are more noticeable than others. As one can see below, even within the same model of combat smock (e.g., "A" and "B"" = 1966 model, "C", "D" and "E" = 1968 model), a surprising variety of sub-patterns can be seen.

Using one particular feature that I would like to call "Fishing Eagle", one can readily note the many similarities and differences between these DPM variants, which can be grouped into four major types:

1) Fat bird: A, F, K, M, N. O

2) Skinny bird: E, J

3) Fuzzy bird: B, C, D, I

4) Broken leg: G, H, L

Within these four major types, a number of subtypes can be differentiated based on features, in ways that are far less subtle than what helmet and medal collectors are accustomed to seeing when identifying various decals and pin shapes.

What is clear from this comparison is that the Dutch DPM ("N", and its New Zealander cousin "O") is a virtual copy of one sub-type of DPM pattern that appeared on 1968 model British combat uniforms, which was itself a derivative of one variant of the DPM patterns seen on 1966 model uniforms. It is readily distinguishable from the last pattern DPM in British service ("H"). As near as I can tell, the Dutch military adopted only one pattern and never made changes to it.

I am not sure why the UK designers felt the need to play with the DPM pattern so much over the years, since most of these differences begin to disappear at any distance beyond arm's length. Perhaps they thought they were designing collectibles for future generations of militaria enthusiasts?

Incidentally, I truly believe the 1968 model smock was the best combat jacket ever made, at least in terms of its design and build quality, as well as casual-wearing comfort. They are still relatively cheap and plentiful from ordinary surplus sources; I don't seem to be able to stop myself from buying more of them whenever I come across any, because "they" simply don't make'em like that anymore...

Gene T

Anyone looking for an exhaustive analysis of the Bundeswehr's use of DPM type camouflage as applied to the "Bristol" Type Body Armor need look no farther than this excellent thread.

All the best - TJ

Comment

Users Viewing this Thread

Collapse

There are currently 3 users online. 0 members and 3 guests.

Most users ever online was 10,032 at 08:13 PM on 09-28-2024.

Comment